Although there are tools to create simple algo trading systems without coding, there's normally no way around code for serious algo trading development. Strategy coding (or programming) is the act of writing the rules of an algorithmic trading system in code - a sort of simplified language. The simplest way to code is applying artificial intelligence. Youi can use the ChatGPT coding mentor with the follwing propt:

"Write a strategy that uses two moving averages (SMA) of the Close price.

When the SMA(30) crosses over the SMA(100), open a long position.

When the SMA(30) crosses under the SMA(100), open a short position.

Ue a stop at 10 pips distance."

This creates the following code (or similar):

function run()

{

vars Prices = series(priceC());

vars SMA100 = series(SMA(Prices,100));

vars SMA30 = series(SMA(Prices,30));

Stop = 10*PIP;

if(crossOver(SMA30,SMA100))

enterLong();

if(crossUnder(SMA30,SMA100))

enterShort();

}

But just as with visual coding tools, ChatGPT is only suited for rather simple strategies. If you wanr to write a system that exploits a particular market inefficiency, you have to write code yourself. Zorro uses C or C++ for algorithmic trading, because they are the fastest and most widely used high-level languages. A script in C/C++ will need only a few seconds for a 10 years backtest. The same script in R or Python would need hours for the same task. Most software today is written in C or C++, and most trading platforms use C or a C variant for automated trading. Zorro gives you the choice to develop strategy scripts either in lite-C, a 'lightweight' version of the C programming language, or in 'full grown' C++.

The lite-C compiler does not require a linkage process and thus compiles and starts a script 'on the fly'. It also includes a framework that hides away the complex stuff - like API calls, pointers, structs, etc. - that is difficult to beginners. It was originally developed for the computer game company Atari for controlling the artificial intelligence of agents in computer games. As you can imagine, a language powerful enough to control simultaneously ten thousands of agents in a virtual world is an excellent choice for trading strategies. Since most languages have a similar structure, after learning lite-C you'll also be able to understand simple code in Python, Pascal, or Tradestation's EasyLanguage, even though the latter declares a variable not with var x = 7, but with Vars: x(7).

The following workshops give a quick introduction into coding algorithmic trading strategies and indicators. They are for the language C, but the same scripts in C++ would look almost identical. The differences are listed under Coding in C++. For a more in-depth introduction to the Zorro platform, the C language, and algorithmic trading methods, get the Black Book.

The example strategies are for educational purposes only and designed for simplicity, not for maximum profit and minimum risk. For trading with real money, better develop your own strategies.

A script (or program) is a list of instructions in plain text format that tell the computer what to do under which circumstances. It consists of two types of objects, variables and functions (C++ has a third object type, classes, that are a combination of both). A variable is used to store numbers, text, or other information. It must be defined before it can be used, like this:

var Price;

int Days = 7;

string Wealth = "I am rich!";

Variables can have different types for different purposes, such as var (or double) for prices, vars for a time series, int for counting, or string for text. You can find details about the different types here. Any variable can receive an initial value at start.

A language that controls a certain platform, such as Zorro, has normally also predefined variables that affect the behavior of the platform. For instance, the Stop variable in the above SMA crossing example is used for setting up the stop loss distance. Predefined variables need not be defined by the user.

We can add comments to explain our code, using two slashes:

int CandleHeight; // the height of a candle in PIP

Often in testing a script we temporarily disable a line by placing two slashes in front of it. This is "commenting out" a line, and is used so frequently in programming that the script editor has two extra buttons for commenting out and commenting in.

Every definition or any command in C needs to end with a semicolon. If you forget to add ";" at the end of the line of code, you'll see an error message - not for the line with the missing semicolon, but for the following line!

Start Zorro, select Workshop1 in the Script dropdown menu, then press [Edit]. The script editor opens up and shows you this script:

// Tutorial Workshop 1: Variables

////////////////////////////////////////

function main()

{

var a = 1;

var b = 2;

var c;

c = a + b;

printf("Result = %.f",c);

}

The script begins with a comment (the lines beginning with //). Then we have a function named main - anything that happens in a program must be inside a function - and three variables a, b, c. The action happens in the following line:

c = a + b;

This tells the computer to add the content of the variables a and b, and store the result in the variable c. The last line displays the content of c in the message window:

printf("Result = %.f",c);

Now press [Test] on Zorro's panel and watch the script running.

Functions can be defined using the word function (or void, or a variable type, more about that later) followed by the name of the function and a pair of parentheses ( ). The parentheses are used to pass additional variables to the function, if required. The body of the function is written inside a pair of curly brackets { }. The body consists of one or more lines of C code that end with a semicolon. Programmers usually indent the code in the function body by some spaces or a tab, for making clear that it is inside something.

Zorro scripts often use the convention of lowercase names for functions (except for common indicators such as EMA), 'CamelCase' for variables (except for 1-letter variables with no particular meaning like a, b, c, or indices like i, j, k), and UPPERCASE for #defines and flags (which we'll explain later). An example of a function that computes the number of days spent by me (or you) on Earth:

function compute_days()

{

var MyAge = 33;

var DaysPerYear = 365.25;

var NumberOfDays = MyAge * DaysPerYear;

printf("I am %.0f days old!",NumberOfDays);

}

Enter this code in a new empty script, and save it (File / Save As) into the Strategy folder under a name like Myscript.c (don't forget the ".c" at the end - it means that this file contains C code). You should now find Myscript in the Script scrollbox. When you now select it and click [Test], you 'll get an error message "No main or run function!".

If a function is named main, it will automatically start when we start the script. Just like predefined variables, there are also predefined functions. The most often used is run that normally contains the trade strategy and is automatically run once for every bar period. If a script has neither a main nor a run function, Zorro assumes that you made a mistake and will give you this error message.

So enter a main function at the end of the script:

function main()

{

compute_days();

}

This code calls (meaning it executes) our compute_days function. Any function can be called from another function, here from the main function. For calling a function, we write its name followed by a pair of parenthesis and the ubiquitous semicolon. Write the code for your functions first and and the code that calls them later. The computer reads code from the top of the script down to the bottom, line by line. Don't call or refer to something that was not defined before, or else you will get an error message. The printf function is a special function that displays something in the message window.

You will likely encounter compiler errors when you write scripts - even experienced programmers make little mistakes all the time. Sometimes it's a forgotten definition, sometimes a missing semicolon or bracket. Get used to compiler errors and don't be helpless when you see one. The computer usually tells you what's wrong and at which line in the script, so you won't need rocket science for fixing it.

A function can also get variables or values from the calling function, use them for its calculation, and give the resulting value back in return. Example:

var compute_days(var Age)

{

return Age * 356.25;

}

The var age between the parentheses is for passing a value to the function. This is our new script with passing variables to and from functions:

var compute_days(var Age)

{

return Age * 365.25;

}

function main()

{

var MyAge = 33;

var NumberOfDays = compute_days(MyAge);

printf("I am %.f days old!",NumberOfDays);

}

The "I am %.f days old!",NumberOfDays are the two variables that we pass to the printf function. The first variable is a string, used for displaying some text: "I am %.f days old!". The second variable is a var: NumberOfDays. Check out the printf function in the manual.

When a function returns a var, we can just place a call to this function in stead of the var itself - even inside the parentheses of another function. We'll save one variable and one line of script this way::

function main()

{

var MyAge = 33;

printf("I am %.f days old!",compute_days(MyAge));

}

!! Important tip when you call functions in your code that return something. Do not forget the parentheses - especially when the parameter list is empty! In C, a function name without parentheses means the address of that function in the computer memory. x = add_numbers; and x = add_numbers(); are both valid syntax and normally won't give an error message! But they are something entirely different.

You will use "if" statements when you want your script to make decisions - meaning that it behaves differently depending on some conditions, like user input, a random number, the result of a mathematical operation, a crossing of two indicators, etc. Here's the simplest form of the "if" statement:

if(some condition is true)

do_something(); // execute this

command (a single command!)

or:

if(some condition is true)

{

// execute one or several commands that are placed inside the curly brackets

}

else

{

// execute one or several commands that are placed inside these curly brackets

}

A practical example:

function main()

{

var MyProfit = slider(3,50,0,200,"Profit",0);

if(MyProfit > 100)

printf("Enough!");

else

printf("Not enough!");

}

When you click [Test] to run that script, you'll notice that the bottom slider gets the label "Profit". Move it all the way to the right, so that 200 appears in the small window, and click [Test] again. You can see that the result is now different. The slider() function has put its return value - which is the value from the bottom slider - into the MyProfit variable, and thus the if(..) condition became true as the value was bigger than 100. You can see details of the slider function in the manual.

An example of a "while loop":

while(MyMoney < 1000000)

trade(MyMoney);

The while statement has the same syntax as the if statement. A "loop" is called so because the program runs in a circle. Here's the form of a while loop:

while (some condition is true)

{

// execute all commands inside the curly brackets repeatedly until the condition becomes false

}

Whatever those commands do, they must somehow affect the while condition, because when the condition never changes, we have an "infinite loop" that never ends! Run this in Zorro:

function main()

{

int n = 0;

while(n < 10) {

n = n + 1;

printf("%i ",n);

}

}

This little program adds 1 to the variable n, prints the variable to the message window, and repeats this until n is 10.

Loops are very useful when something has to be done repeatedly. For instance, when we want to execute the same trade algorithm several times, each time with a different asset. This way we can create a strategy that trades with a portfolio of assets.

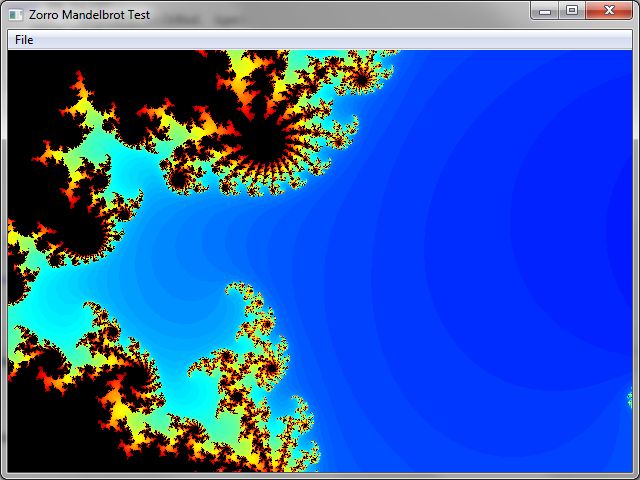

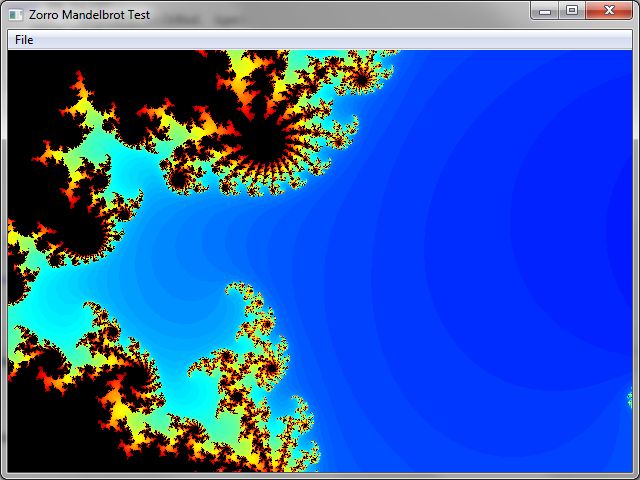

We are now at the end of the basic workshops that teach general coding. But we haven't touched yet concepts such as macros, pointers, arrays, structs, classes, or the Windows API. You can learn 'real' programming beyond the scope of trade strategies with a C book or a free online C tutorial, such as Sam's Teach Yourself C in 24 Hours. You can also join the Gamestudio community that uses the lite-C language for programming small or large computer games. Check out how a 'real' C program looks like: open and run the included script Mandelbrot. It has nothing to do with trading and you will probably not understand yet much of the code inside. It is a normal Windows graphics program. Don't worry, trading strategies won't be this complicated - it just shows that programming can be a lot more fun even without earning money with it.

In the next workshops we'll begin developing trading strategies.